Far before television and the internet existed as the film buff’s main source of media/film news, there existed a far more primitive but personal avenue for staying up to date with the day to day happenings of the Hollywood scene. Although it seems that the paper magazine is moving closer and closer toward extinction, it appears to be finding clever ways of utilizing new forms of technology. E-readers, film websites, and tabloid television are just a few of the modern mediums influenced by classic film journalism. Understanding why print film journalism was so effective during this golden age of cinema starts with taking a closer look at a few specific magazines from the era. Still two of the hottest Hollywood magazines to this day, Variety and The Hollywood Reporter have established themselves as reliable pillars of the film news community. Like a sort of tabloid darwinism, only the strongest magazines survived. Magazines such as Photoplay and Motion Picture News, whether losing swiftly or taking a prolonged stand, eventually faded into nonexistence. The various types of stories, perspectives, advertisements, and readers that these magazines encompassed helped to represent a budding film industry that was quickly taking over as the world’s number one form of artistic entertainment. Although each of the four magazines mentioned have many elements in common, the differences are what make them unique. (Hoover, pars. 2-4)

Taking an initial look at The Hollywood Reporter, it is quite surprising how barebones the magazine is in terms of art. I expected a much more vibrant and artistic cover, but The Hollywood Reporter never built its success on being a flashy magazine. The magazine is presented in a format that most modern readers would mistake for the classifieds section of their local newspaper. Although the magazine isn’t eye-catching by today’s standards, the reporting certainly is. The reporters seem to have taken extra pride in reporting the facts in a concise and colorful way. The color scheme also seems to lure the film lover into picking up the latest issue. Black and red are the only two colors used, but the latter is used sparingly to accent titles, advertisements, or other information thought to be of utmost importance to the reader(or studio). Overall, The Hollywood Reporter seemed truly focused on reporting the real news of Hollywood as opposed to tabloid gossip. (Wilkerson, 1)

Taking a step back to December of 1905, the first issue of Variety hit the newsstands. By today’s standards, the art style in the 1933 Hollywood Reporter is lacking. The art style for the first issue of Variety is nearly nonexistent. The words are microscopic and fill entire pages with absolutely zero grace. The artistic development in magazine layouts over the course of 28 years is clear when comparing Variety to The Hollywood Reporter. Of the two, Variety seems to be more focused on the lives of various important entertainment figures, dipping its toe slightly into a more gossipy tone. It looks like yet another piece of evidence that proves even our ancestors couldn’t avoid the rumor mill. (“Variety,” pg. 1-3)

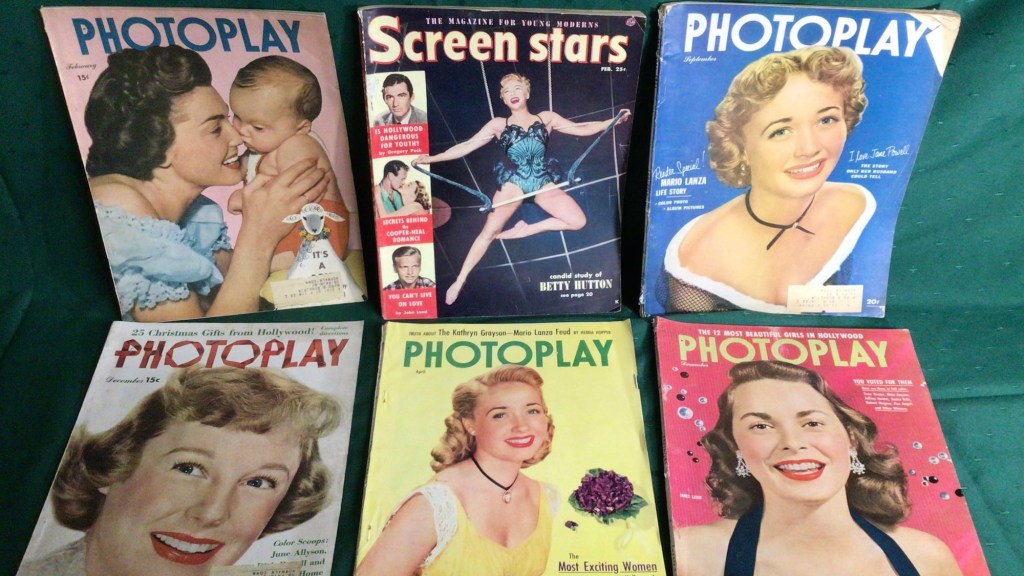

In between the releases of the 1905 Variety and the 1933 Hollywood Reporter, a much more colorful and photography filled magazine was released. When taking a look at a copy of Photoplay from the end of 1917, it is clear why this magazine was so popular during this time period. There are pictures on nearly every other page. Although a majority of the pictures that fill the pages are just some kind of advertisement, some seemed to be photoshoots that featured a current popular performer. Compared to Variety and The Hollywood Reporter, Photoplay seems more focused on entertaining the reader as opposed to informing them. (Quirk, 1-10)

Jumping ten years to 1928, a copy of Motion Picture News proves that distinct art styles are an extremely important aspect of entertainment magazines. When looking at Photoplay next to Motion Picture News, it is abundantly clear that even though these magazines take a similar approach, their art styles are distinctly unique. Similar to the color scheme of The Hollywood Reporter, Motion Picture News features mostly black print accented by red highlights (with some blues thrown in there occasionally). What is truly unique about Motion Picture News is that its art style is much more in your face than the other three magazines. It almost feels like the visual equivalent of someone yelling at you through a megaphone. Planes, fists, and people fly across the page, using the illusion of movement to somehow make reading a magazine extremely energetic. So it’s very clear that each magazine during this era distinguished themselves in various artistic ways, but what makes each one truly unique are the different stories that they tell from varying perspectives. (Johnston, 1-5)

Looking at each magazine in order of release, the evolution of stories and perspectives in these magazines becomes quite clear. After being fired by The Morning Telegraph in 1905, Sime Silverman decided to start a publication Variety that he claimed would not at all be influenced by advertising. Before the explosion of the cinematic tradition throughout the world, entertainment workers didn’t seem to achieve the level of fame that modern day celebrities hold. They had to find their job opportunities in newspapers just like everyone else. That’s why the ads that are often found in publications such as Motion Picture News are aimed directly at the common actor. Although they were filled with ads, that was sometimes the point. These were the publications that the actors themselves read, keeping in tune with the pulse of the industry. When the industry began to move away from this type of working model, those publications began to fade in popularity. When comparing Variety to Photoplay or Motion Picture News, the distinction that Variety avoids advertising became infinitely clear. Variety and The Hollywood Reporter are much less visually interesting than other magazines of the time, but their reporting/stories seem much more important (or at least the writing makes one feel that way). It’s no wonder the two magazines that focused on quality stories would be the two that are still around to this day. The flashy and advertisement filled magazines had popularity but not necessarily longevity. (“History of Variety,” pars. 1-3)

So looking at the 1917 copy of Photoplay, the distinction between informative entertainment news magazines and magazines meant to solely entertain becomes abundantly clear. Excluding the cover, the first three pages are exclusively advertisements. It is honestly no wonder magazines such as this eventually faded into irrelevance. After the novelty of a magazine filled with pretty pictures wore off, most readers probably realized the Hollywood themed content they were consuming was only skin deep. After the first three ads, you come across the table of contents. After that, four more pages of advertisements. (Quirk, 1-7) This seems like the equivalent of having to watch 3 advertisements before a Youtube video and then having to watch 4 more 1 minute later. In the modern day, any entertainment outlet that would attempt to shove that much advertising down their consumer’s throat in such a short period of time would be considered embarrassingly shameless. Eventually all the advertising leads to a string of pages that include photos and brief biographies of various female movie stars. This magazine seems clearly marketed for the readers who had a tendency to lean toward more gossip-toned articles. It is easy to imagine the readers of Photoplay as poverty stricken midwesterners who daydream of living the lives of their favorite movie stars. That being said, the information the magazine gives seems reasonably accurate. Photoplay is also the longest of the 4 magazines by about 50 or more pages, just proving that whoever read this must’ve had a lot of extra time on their hands. (Doyle, pars. 2-10)

Jumping forward to 1928, Motion Picture News is also filled with heavy doses of advertising. This time though, the advertisements stick firmly to advertising only movies, movie studios, or something else movie related. The second page even has advertisements for films such as 1927’s Wings. Motion Picture News appears dead set on advertising the film industry and nothing else. The only true articles are in the editorials section of the magazine. Out of the 4 magazines analyzed in this essay, I expect most readers to find Motion Picture News to be the most appealing overall. It has a nice mix of visually interesting film advertising and informative editorials. It also stays firmly on topic. Nothing unrelated to film seems to touch even an inch of the page.

Looking at a copy of The Hollywood Reporter from 5 years later in 1933, it is truly stunning to see the different approaches to film reporting. Very appropriately, The Hollywood Reporter places the most important news articles of the day front and center. It clearly says to the reader that this magazine doesn’t waste time with wacky visuals (excluding the occasional holiday issue). They’re here for the news and the news only. The rest of the magazine is filled with information on upcoming films and films currently in production. This seems like the type of magazine that people currently involved in the industry would read. It doesn’t feel the need to glamorize Hollywood because a majority of their readers already know the truth anyway. The Hollywood Reporter is also significantly shorter than any of the other 3 magazines. It seems as if they truly cared about their content, and like Variety eliminated most advertising within their magazines. Again, it seems to have worked out in their favor. (Di Mambro, “Vintage Hollywood Magazines”)

Photoplay is the only magazine of the four that seems to allow any kind of advertising. It seems that advertisers believed only bored housewives read magazines. The inherent misogyny of the times is unfortunately palpable in the pages. Half of the advertisements feature a hardworking woman cleaning or cooking something. Wax, necklaces, diamonds, and soap are just a few products advertised in the early pages of Photoplay. Motion Picture News seems to hold just as many advertisements as Photoplay, but like stated earlier, Motion Picture News’ advertisements stuck firmly to featuring film related products and people. The closest thing to advertisements that Variety had were the classifieds for agents on the last page, also staying loyal to the tradition of meaty information with most of the fat trimmed away. The only true advertisement to be found in this issue of The Hollywood Reporter was one page dedicated to advertising the unmatched prestige of Paramount Pictures. Regardless of how much advertising was used, it seems that each magazine found success in each of their respective eras. Motion Picture News, which seemed to be the most well rounded of the 4 magazines, had the shortest lifespan. Variety and The Hollywood Reporter are still in print today, Photoplay ended in 1980, and Motion Picture News only ran until 1930. The likely reason seems to be that the others had clearly defined audiences. Motion Picture News seemed as if it could decide whether its target audiences were the people who made Hollywood or the people who consumed it. (“Early Advertising of the West, 1867-1918,” pars. 1-6)

Judging by the vast variations in magazine styles between 1905 and 1933, entertainment news was developing right along with the swiftly changing film industry itself. It seems that during this time there was an almost oversaturated market of film news magazines. Although some approaches ended up working better than others, each one had its own unique spin on reporting film gossip/news. The varying stories, perspectives, advertisements, and target audiences that these magazines feature leaves no doubt as to why film gossip/news are still some of the most popular forms of movie themed entertainment to this day. Maybe that’s because the world has never stopped loving movies and most likely never will.

Works Cited

Di Mambro, D. (n.d.). Vintage Movie Magazines — A Gallery. Retrieved April 1, 2021, from http://www.classichollywoodbios.com/vintagemoviemagazines.htm

V. (Ed.). (n.d.). History of Variety. Retrieved April 1, 2021, from https://variety.com/static-pages/about/history-of-variety/

U. (2008). Early Advertising of the West, 1867-1918. Retrieved March 28, 2021, from https://content.lib.washington.edu/advertweb/index.html

Hoover, T. (2014, February 27). Going Hollywood: Movie Fan Magazines. Retrieved April 1, 2021, from https://www.thehenryford.org/explore/blog/going-hollywood-movie-fan-magazines

Doyle, J. (2019, February 5). Talkie Terror. Retrieved April 1, 2021, from https://www.pophistorydig.com/topics/tag/photoplay-magazine-history/

Wilkerson, W. (1933, January 3). The Hollywood Reporter. The Hollywood Reporter, 12(36), 1-10. Retrieved March 28, 2021, from https://archive.org/details/hollywoodreporte1215wilk/page/n3/mode/2up?view=theater

C. (Ed.). (1905, December 16). Variety. Variety, 1(1), 1-16. Retrieved March 28, 2021, from https://archive.org/details/variety01-1905-12/page/n15/mode/2up?view=theater.

Quirk, J. R. (Ed.). (1917, October). Photoplay. Photoplay, 1-10. Retrieved March 28, 2021, from https://archive.org/details/phooct1213chic/page/n6/mode/1up?view=theater.

Johnston, W. A. (Ed.). (1928, October 6). Motion Picture News. Motion Picture News, 38(14), 1-10. Retrieved March 28, 2021, from https://archive.org/details/motionpicturenew38moti/page/n3/mode/2up?view=theater.

T. (Ed.). (1934, January 2). The Hollywood Reporter Holiday Issue. The Hollywood Reporter, 18(42), 1-10. Retrieved March 28, 2021, from https://archive.org/details/hollywoodreporte1821holl/page/n5/mode/2up?view=theater.